EDITING, UM, DIALOGUE

Have you ever listened to a podcast that felt a little too polished? Or, the opposite is true, and you can’t focus on the story because it’s been poorly recorded and edited? It turns out, humans have incredible ears for noticeable or bad edits. You don’t need formal training to recognize when something sounds unnatural to your ears. Without thinking, we’re always listening to speech patterns and the rhythms that go hand-in-hand with dialogue in our everyday lives. And when someone creating a podcast edits dialogue too heavily and inadvertently removes what makes the speech human, it’s immediately noticeable. I personally find that if I can spot edits when I’m listening to a podcast, I can’t focus on the content itself. I get too distracted by how the content is being delivered to allow myself to become fully immersed in what I’m being told.

I’m a sound designer here at Pacific Content, so I am constantly thinking about the pacing and rhythm of not only the episodes as a whole but the individual guests and scenes within one. One of the first things I do when I’m working on a dialogue edit is listen to the raw tape.

I sit and close my eyes and focus on just the tape. I listen to how fast the speaker talks, I listen to how often they take a breath during their sentence, and I listen to the cadence of their speech pattern.

Then, once I feel like I can hear their natural voice in my head, I go back to the assembly that I’m working on to smooth out the cuts and listen for anything that doesn’t really match their natural voice.

Step 1: Pacing

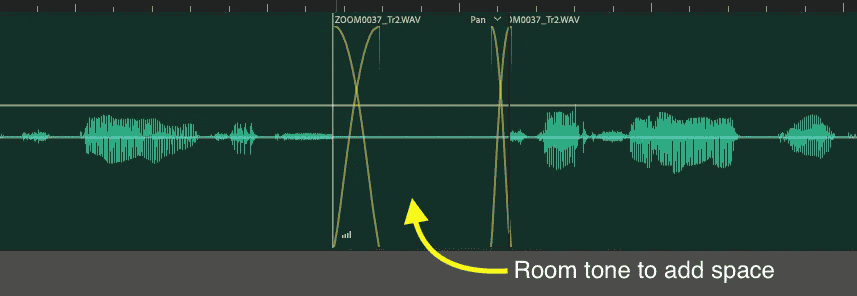

If I find a spot in the rough assembly where the words feel jumbled together, I will add room tone to help space the words ever so slightly.

If I hear what sounds like a run-on sentence, I will try and find a natural breath to add; my rule of thumb for bringing in a breath and making it sound natural is using an already occurring one at the end of a word and cutting that new word in at the end of the natural breath. It’s a lot easier to smooth out than trying to blend the start of a breath with the end of a word that didn’t come before it. But if that’s not possible in the sentence you’re working on, room tone will help a lot in smoothing out an added breath.

Step 2: Intonation and Meaning

Pacing isn’t the only important part of smoothing out a cut — spaces between words and breaths are essential to get right. But that’s not the only thing our ears pick up on. The other critical part of a dialogue edit is the intonation. When you speak, you often add emphasis to words and sentences by using intonation: a change in pitch to signal attitude or emotion or even a difference of meaning.

A great example of this is how we understand a sentence to be a statement or a question. If you say “It’s 3 o’clock.” versus “It’s 3 o’clock?” out loud, you should notice that you end the statement sentence in a definitive sounding falling intonation. Whereas when you say the question statement out loud, it’s usually expressed with a rising intonation.

Sometimes it’s tempting to try and make a content edit, but if the intonation is mismatched you will immediately hear the difference.

If it’s only one word that is throwing off the cut, I will sometimes try to find an alternative in the raw tape to use instead. This can be really tedious but is made a little easier by using a transcription tool that allows you to do a text search. Two of the tools I’ve worked with and found useful are Descript and Otter.ai.

It’s also important to note that I would only ever use this technique to replace a word that was already used in the original statement, but never to find a different phrase to cut in. Making sure to maintain the original meaning of the sentence is an absolute must. In recent years, there have been examples of people using tools to create words that were never said aloud. I strongly believe that the AI tools being developed to re-create speech should never be used to create a brand new statement that gets attributed to your interviewee. Although it’s possible to do, as we saw recently with the Bourdain documentary, creating new content and attributing it to your subject is ethically problematic.

Step 3: Uh, Um, Err

Beyond smoothing edits for cadence and intonation, there is an ongoing debate within the audio world about cutting filler words and sounds, such as “like,” “um,” and “uh.” I’ve had this discussion a number of times with engineers and producers alike. Some folks prefer to try and cut every utterance of a filler word to make the audio as clean as possible. Others prefer to leave them as is. I personally fall on the side of making your end product sound as true to the person speaking as possible. So I typically will opt to leave in a handful of filler words, because removing them completely makes people sound scripted. It takes a very practiced speaker to not use any filler words in their regular speech and my preference is not to overdo the cleanup.

Additionally, you may notice that it’s difficult to trim out all of the filler words anyway because people tend to say them in very close proximity to their next thought, and as a result affect the rhythm of their next statement.

Step 4: Review

Once the basics of the speech in your edit have been cleaned up, it’s important to go back through and listen closely. I am a strong believer of the “eyes-closed” method. I find that I’m better at discerning problems in my edits when I am not watching the playback. If I can see where an edit is I tend to hear it differently than if I just listen. At this point, I want to make sure that I don’t hear any audible shifts in pacing, or intonation, or cadence in general. But I also want to use this listen to really hear what the person is saying. If your host or guests are speaking for a long period of time, you might want to introduce intentional pauses to allow your audience to digest what has been said. Eventually. this could be where you add in music or scene sound effects, if it works as an effective place to emphasize meaning. But for the dialogue edit, it’s helpful to really listen to the content and identify where you might naturally take a beat before continuing to speak.

Final thought

Speech can be difficult to edit without changing the intention or losing the natural voice of the actual person speaking. I think it’s important to always make sure to listen back and ask yourself “does this sound natural?” because you want your audience to hear what you’re saying with your podcast, not how it’s made.

Sign up for the Pacific Content Newsletter: audio strategy, analysis, and insight in your inbox.