For the Love of Sound: the Art & Science of Listening

Most humans interact with sound on a subconscious level. As an audio engineer and sound designer, I’ve never interacted with anything more consciously.

Before coming into this career, I spent my life as a consumer of sound. I was addicted to the way sound made me feel, which I assume is how I ended up here (at Pacific Content). Not knowing much about audio from the get-go, I often relied on my instincts and learned to trust my ears and trust what I was hearing to guide me.

When you work with audio, everything you do is reactionary based on how you perceive the incoming source. Decisions made strictly based on taste are subjective, but there are over a hundred years of science that suggest some of those choices we make are actually objective.

As it turns out, sound designing is incredibly scientific. Psychoacoustics is a branch of psychophysics that explores how humans (and non-humans) perceive sound and our physiological responses to it.

Why do sound designers care about psychoacoustics?

I am infinitely intrigued by the fact that we can’t really determine what something sounds like because we can only hear what our ears perceive. As audio professionals, we have to trust that what we hear is what the majority of the population will also be able to hear.

Understanding some of the basics of how humans hear, we can elevate our mixes, and hopefully, make them more enjoyable for the listener.

1. Human hearing has limitations

The average human can hear a range of 20Hz–20,000Hz. Typically as we age, we’ll start to lose the upper range of our hearing, leaving us with a range up to 16,000Hz. For reference, an 808 kick drum would resonate at around 50Hz-100Hz, so 20Hz is already very challenging to hear, and is more often felt.

I highly recommend regular visits to an audiologist to get your hearing tested. It’s important when you’re working with sound to understand any potential weak points you might have so you can compensate for them.

2. Our Ears are Natural Equalizers

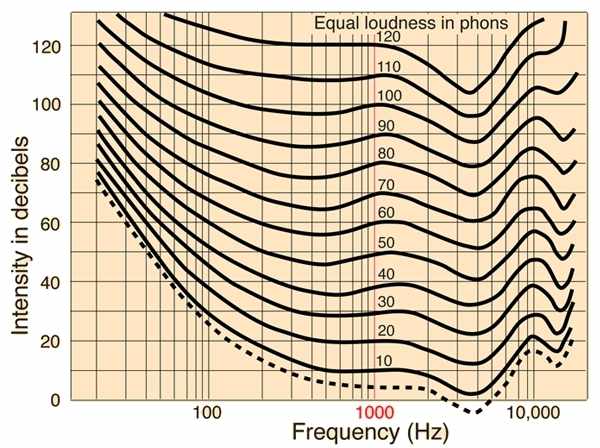

If we played 100Hz at 10dB and then 2.5kHz at 10dB, we would not perceive these two signals to be the same volume. The Fletcher-Munson Curves show that our hearing is sensitive to loudness throughout the frequency range. If you’re listening to a sound mix at a lower volume, you will hear much more of the midrange sounds and way less of the low and high-end sounds. A quiet listen through your mix can be a great perspective shift.

This also plays a huge role in mixing dialogue and voices in a podcast. You could be using the exact same processing chain for two different guests but because each person speaks at a different frequency, one guest may appear to be much louder and more present in your mix than the other. In this case, you’d need to listen intently and make a few adjustments based on that individual’s voice.

3. The Importance of the Middle Ear

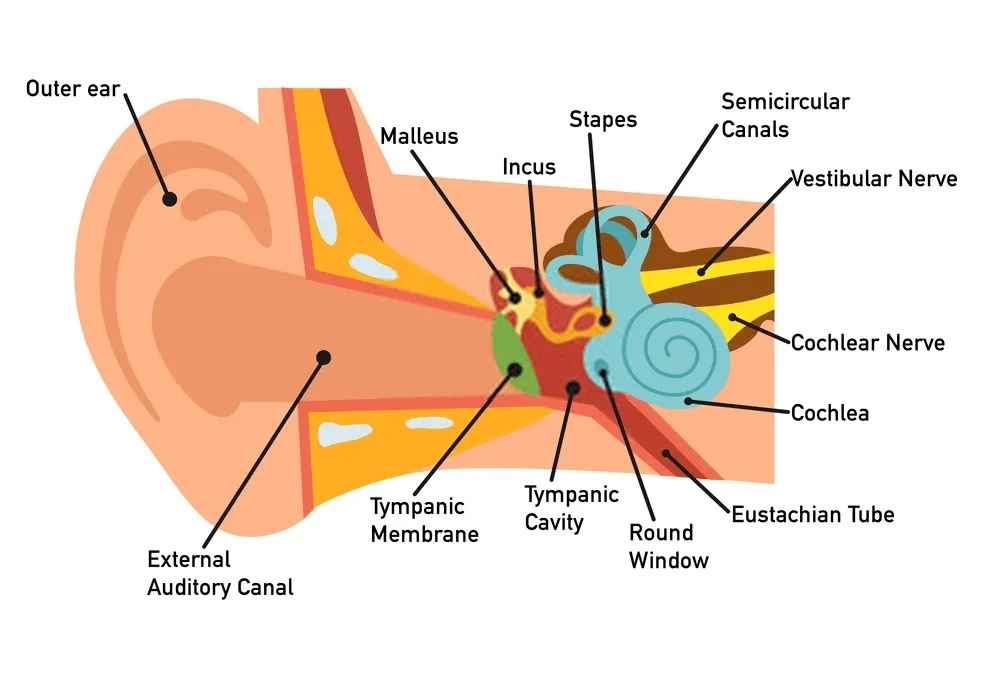

The part of the ear that fascinates me the most is the tympanic cavity, more commonly known as the middle ear. You guessed it, between the outer and inner ear is an area called the middle ear. It contains three little bones (called ossicles) that transfer vibrations from the eardrum into waves in fluid and membranes of the inner ear.

Because we’re used to hearing this way subconsciously, sound designers have started to use this as a natural technique when needing to recreate the sound of an explosion or gunshots on screen. The initial noise is very loud and ducked immediately because your brain will perceive it as the same volume without actually doing any damage to your hearing when you are watching a movie in a theatre or listening to media through headphones.

Understanding how we hear has had an immense impact on the media we put out to the world.

We all care about psychoacoustics (whether you realize it or not)

Our ears have evolved in a way that is designed to protect our hearing, a precious sense. Whether you work in sound or not, recognizing the power of hearing is crucial. Over the years, the study of psychoacoustics has led to more questions, which has led to more discoveries.

The discovery that I’ve found most beautiful and relevant is music therapy. Obviously, music can be therapeutic. It can help relieve short-term anxiety and even help us focus. I’m sure music has been used in a therapeutic context long before we understood the science of psychoacoustics. Music therapy, however, is a little different.

Registered music therapists work with patients to address physical, cognitive, and emotional needs. For example, it’s becoming an increasingly more popular treatment for people who suffer from Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Music is made up of different elements (pitch, melody, rhythm), and your brain processes these elements differently. As we’ve listened to music and sounds over the years, we’ve created emotional attachments with them, engaging our limbic system. When we hear these sounds again, our limbic system can be reminded of the memories associated with the music.

For example, a study technique that students have used is listening to the same playlist or type of music when it comes time to study because their brain has associated those sounds with focus and study time. Because music involves so much of the brain and body, studies have shown that music has the ability to activate neurological pathways that language alone cannot connect.

Even patients in the late stages of dementia have shown more vocal activity, physical movement, and facial expression changes through music therapy.

Each day, I wake up grateful for my ability to hear. It’s the way that I both connect and disconnect from the world. Your hearing should not be taken for granted, I encourage everyone to protect their hearing any way they can. Protect your ears; it’s not wrong to plug your ears if an ambulance passes you on a walk, it’s not wrong to wear earplugs to concerts or loud bars.

Our ears bring great value to our everyday lives— winding up or down with a favourite song or podcast, waking up to the birds chirping outside your window in the morning, or being alerted, when you were just a kid, by the sound of that garage door when your parents arrived home—sound has the ability to bind us to a time, place, and feeling in small and big ways.

Sign up for the Pacific Content Newsletter: audio strategy, analysis, and insight in your inbox.