Recording in the Field

It was a cold, gray Friday in March of 2020 when I was told, along with millions of others around the world, to shelter in place. That first lockdown of the pandemic, and subsequent lockdowns, showed us all just how much we might have taken for granted before Covid-19. The ability to travel or visit with friends. Or working a public-facing job without putting your life at risk.

Something that I had taken for granted (though it took me a long time to realize just how much) was recording in the field. Whether that was walking around neighbourhood locations to capture ambient sound, traveling to other places to record interviews or live events, or simply hiring a freelancer to be my surrogate microphone while I listened in over Skype. As the months, and years of lockdown dragged on, my colleagues and I got used to doing everything remotely and mostly over Zoom.

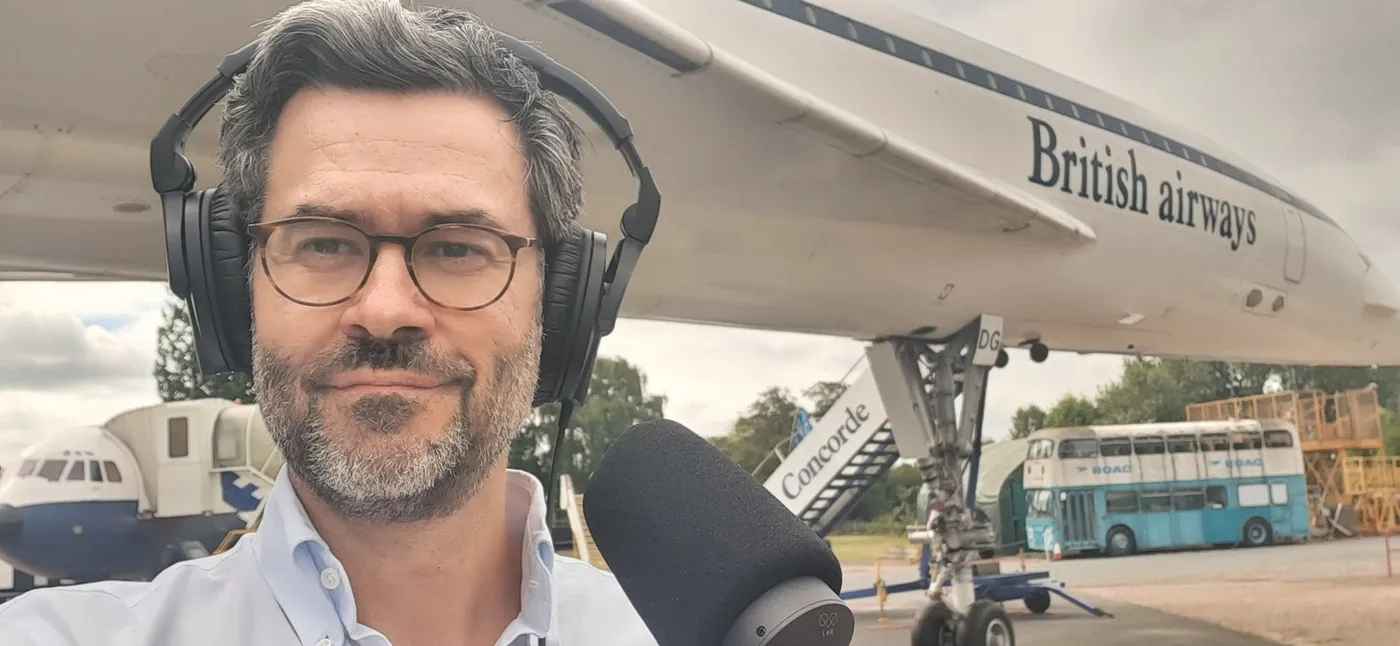

But it wasn’t until I returned to the field — a week last August in Britain and France to work on our Concorde series — that I realized how much we had missed. And not just what was missed, but how rusty I had become at field recording. I had to remember a lot of the lessons I’d learned long ago, and in the process, learned a whole bunch of new stuff.

Before I headed out, I spoke with a number of my colleagues to get their advice. And damn was it helpful. I had already sketched out who I was going to speak with on my trip: former Concorde workers at a few museums around Britain and France. I wanted to speak with them about facts — how the plane worked, etc — while onboard the plane. But I also wanted to ask them about their emotions and memories. Should I do that in the plane as well, or in the loud, busy museum hall? The response was dead simple: find a quiet room. Do the in situ interview walking around and inside the plane, of course. But then, later, take our guests to a quiet space and dig into their personal stories. Which I did with everyone.

The conundrum I had was, with all these interviews in so many places, wouldn’t I just come home with a huge jumble of unconnected tape? Was it wise to plan out the series before I’d even spoken to anyone? Another damn good idea came my way: sketch out all the key scenes, for each episode, in advance, based on what I’d learned in my preliminary research. Not only did this give me a running order and an idea, in advance, of how the different episodes would fit together, but it meant that my interview questions could be shaped to fit into and around these scenes. This became a roadmap for the show and the interviews at the same time.

There was one other key piece of advice that I got just before heading out: the power of props. For instance, if I could, I should do interviews in people’s homes. And ask them if they had any “Concorde stuff” to show us. Or bring along photos that we could hand to guests during interviews. This strategy paid off spectacularly, bringing out stories and emotions we wouldn’t have found otherwise.

The last key element to this trip was, of course, recording equipment. And our sound gurus went above and beyond in preparing me for every eventuality. I headed to the airport with a carry-on size hard case full of everything I might need: two standard microphones; a stereo microphone; a binaural microphone headset; a new Zoom F3 recorder I could strap to my wrist (and can’t peak!); a boom pole; a pistol grip shock mount; two desktop mic tripods; massive headphones; cables, cables and more cables; and loads of batteries. Surprisingly, airport security in a number of continents hardly batted an eyelid.

It was once we were on the ground that it hit me why recording in the field is so essential to audio storytelling. Most interviews on Zoom are a transfer of information. And so many podcasts today are transfers of information. Which has its place, but doesn’t always lead to deep, emotional engagement with the listener. To be fair, there is still some of that information transfer happening with in person interviews. Of course, there needs to be. But when you add the interaction between the host and the guest — eye contact, body language — another level of sharing happens. Plus, being at places where events took place can evoke memories much stronger than just sitting at home and trying to remember. Not to mention, serendipity. While completing an interview with a guest and preparing to drive back to our hotel, he mentioned there was another location nearby with a great story attached to it. We zipped over and captured a key moment I hadn’t even anticipated. Or another moment, when interviewing a guest while walking through a busy museum and a tourist came up to us and started conducting his own interview! Audio gold.

There was another benefit to being in the field that hadn’t occurred to me until we got home and started processing what we had recorded: the ability to take the listener along with us to all these different places. Sound effects and narrative description are great, but nothing beats the real sound of someone pulling a heavy stainless steel Concorde model off a shelf or entering a flight deck covered in more buttons and switches than you’ve ever seen in your life. Since audio is the most visual medium, the sound of our movements through these spaces creates a rich scene in the listeners’ minds, which helps engage them. It’s no longer just an idea or a story: now there is a physical location, that they have seen in their mind’s eye, to attach to that thought.

Now that the series is complete and almost fully released, I can’t imagine it without field recording. It’s not just that the series is full of sound from the field. I constructed the series sound first: I let the tape tell me what to do and what story to tell. Without this tape, we would have told a story, but a truncated one. Most of the information would have been there, but missing so much of the discovery, humour, and emotion.

Oh, and one last thing: recording in the field is just plain fun. It reminded me of why I love doing what I do and brought back an energy I’d been missing since that awful day in March. So to paraphrase Glengarry Glen Ross: Always be recording.

Sign up for the Pacific Content Newsletter: audio strategy, analysis, and insight in your inbox.